In Our Own Backyard

EDIBLE GRILLS BBQ EXPERT CHERYL JAMISON

By Marjory Sweet · Photos by Stephanie Cameron

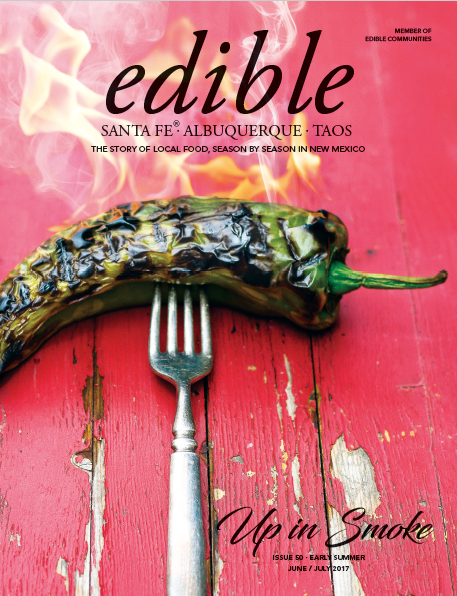

Cheryl Alters Jamison’s particular passion is barbecue—“cooking low and slow over smoldering wood.” Smoke is both an ingredient and the essential technique in the process, she says, “adding its resonance and flavor to the food.”

I didn’t even really eat meat,” Cheryl Alters Jamison admits. As a kid in the Midwest, she learned to love her mother’s Swiss steak, but that was about it. Beef round, slow-cooked with tomatoes and onions, more or less defined her carnivorous worldview. “I thought ‘barbecue’ was just beef with tomatoey sauce.” As a teenager, on a south- bound family road trip, Cheryl ordered a sandwich in Georgia. “Pulled pork with a thin vinegar sauce,” she says. “I was horrified, at first.” It was 1968. To any high-school kid from Galesburg, Il- linois, the sandwich would have tasted exotic. For Cheryl, it was more than just a roadside novelty snack. “The experience made a big impact on me in terms of regional foods.” It wasn’t her first time eating meat, but it was the first time she could connect a distinctive food to a particular place.

Cheryl, alongside her late husband, Bill, would go on to author eighteen cookbooks. Eight of those books focus on either barbecue or grilling, four are James Beard award winners, and one of them, Smoke and Spice, published in 1994, persists as an influential text on home barbecue instruction.

We are sitting on Cheryl’s quiet stone patio in cool, late March Tesuque sunshine. A kitchen herb garden sits next to a wood-burning oven. One of her beloved hens, Margaux, struts in the nearby coop. An oversized grill and other elements of an outdoor kitchen form one corner of the space. A UPS man arrives to drop off a pack- age. “Am I on time for brunch?” he hollers with a smile. “Lots of eggs today!” Cheryl says, letting out a hearty laugh. It is clear this is not the first time this happy, brief exchange has taken place.

The UPS man was delivering a new suitcase. “I figured af- ter 185,000 miles and fifteen years, it might be time to retire the one I’ve got,” says Cheryl. She and Bill wrote and ate their way around the world—literally. In 2009, they published a book called Around The World in 80 Dinners: The Ultimate Culinary Adventure. These days, her luggage isn’t just for clothes: she buys her lard exclusively from Dai Due in Austin and carries it home in her suitcase. Currently, there is fresh duck fat stocked in her fridge. “I used up all the pork fat yesterday making fried chicken for a friend,” she says.

Cheryl first met Bill on her twenty-second birthday when she flew from Illinois for an interview with the Oklahoma Arts Council. Bill was the director. “When I arrived, I was expecting some real conservative bureaucrat. Instead, out bounded lively, long- haired Bill. He seemed like a great ‘older man’ to work for. He was all of 33.” Needless to say, Cheryl was hired. The two married in 1985 and would eventually come to be known as the “king and queen of grilling and smoking,” according to Bon Appétit. Until Bill’s death, they collaborated on travel, writing, lectures, and all things food-related. Bill died of complications from cancer in March 2015; he was seventy-three.

In the eighties, Cheryl worked for the Western States Arts Foundation. She was often on the road for them, raising money and working on various projects. Her work-related travel coincided with the rise of “new American food,” pioneered by now-exalted chefs like Jeremiah Tower, Alice Waters, Steven Pyles, Paul Prudhomme, and Larry Forgione. “People across the country were recognizing what you could do with American ingredients,” she says. “I got to travel during that time and found myself eating in all of these incredible places. That was my culinary education.” In 1983, Bill left the art world to pursue travel writing. Cheryl came along for the adventure and the food. Their eating experiences often ended up in the writing. The Jamisons’ travel writing ultimately became known for its attention to regional foods. “One of the most immediate ways to get a sense of a place is to sit down and talk to people about food,” she says. “People will just open up about it. That was a fascinating part of the process to us.”

When Cheryl finally left her job with the Western States Arts Foundation, she wanted to write some sort of cookbook, as food had become so central to her interests and her work with Bill. At that time, Florence and Laura Jaramillo of Rancho de Chimayó, the generational family proprietors of the historic property, were looking for someone to do a restaurant cookbook for them. The Jamisons had been eating at their restaurant for years. The opportunity to collaborate was obvious. Many plates of pumpkin flan and carne adovada later, the Rancho de Chimayó Cookbook, a small pa- perback, was published. The Jamisons had felt their way through creating a cookbook.

Bill had his PhD in American history, which guided their approach to travel, eating, and writing from the start. “I learned from Bill what to look for,” Cheryl says. Cheryl is interested in regional dishes, meaning food that is defined by place, not popularity. She gravitates to ways of cooking that speak to tradition, not trend. The Jamisons have always been champions of underrepresented foodways. The Chimayó book, for example, revealed a rich, historic cuisine that almost nobody outside of northern New Mexico had been exposed to.

A few years after publishing the Chimayó book, the Jamisons found themselves in Texas. Cheryl recalls stopping to eat on the road and browsing the uniquely Texan offerings—Tex-Mex, barbecue, soul food. “This would be ripe,” the Jamisons thought. “How to tell the story of Texas food.” They quickly realized how difficult it would be to properly address the subject of barbecue in a compendium-style book. Under a section titled “Recipe for Great Texas Barbecue” they considered writing the following: “Pull out your road map, find your way to Kreuz’s Barbecue in Lockhart and eat up.” They were only half joking. “At the time we believed only a grizzled old pit master could do this,” Cheryl says. “You had to have years of experience.” Would it even make sense to write a recipe for making Texas barbecue at home? Was anyone going to actually attempt it?

Around the same time, Cheryl found herself frustrated with the poor instructions that accompanied a little home smoker she had purchased. The Jamisons were in the Houston area and had seen several ads in Texas Monthly for a company called Pitts & Spitts. She decided to call Pitts & Spitts for advice. It happened to be one of the weekends of the Houston Rodeo and Livestock event, and the only person left at the shop was one of the owners, Wayne Whitworth. “Heck! Please come on over! I’m just so bored here by myself.” The three of them started talking about barbecue. The Jamisons wanted to understand the possibilities of smoking food at home. Whitworth was just excited to meet people who were interested in making barbecue. Within thir- ty minutes of conversation, Whitworth said, “How about I bring you one of these pits? I’ll drive it to Santa Fe, stay a week and teach you everything I know.” He kept his promise. His wife had always wanted to see Santa Fe, he told the Jamisons.The newly formed friends spent days and nights smoking everything they could get their hands on: ribs, cuts of brisket, even a ten-pound salmon. They tried different temperatures, varieties of wood, and cuts of meat. “Whitworth was our early barbecue mentor and first champion,” Cheryl says. “He would ask, ‘You want to learn how to cook a whole hog?’ and suddenly we were on our way to Memphis in May, an annual BBQ competition.” After their intensive education with Whitworth, the Jamisons embarked on a “barbecue pilgrimage,” primarily through the South, sampling the many regional styles of brisket, ribs, and pulled pork. These collective experiences culminated in Smoke and Spice, first published in 1994. At the time, most Americans thought barbecue simply meant grilling steaks, and they were largely suspicious of meat cooked for hours at low temperatures. Smoke and Spice was one of the first books to take home barbecue seriously. It was wildly successful. The book is now in its third edition, has sold over one million copies, and is used as teaching text at the Culinary Institute of America. “We had no idea when we stumbled into this [that] it would be such a big deal,” Cheryl says. “We just saw it as a way of paying respect to an under-recognized American food tradition.”

There is an inherent generosity in Cheryl’s excitement toward food. In her kitchen, she is often cooking for others; in her books, she carefully guides readers through recipes and techniques; and in conversation, she offers stories and details of particularly memorable meals. (“Some ghastly bear paws,” she says, when asked about her strangest barbecue experience.) When I first contacted Cheryl, the last thing she had eaten was “Vanilla Vanilla Strawberry, a flan-like dessert of vanilla sauce and strawberry gel at El Nido.” She says there is nothing she won’t eat or drink—except coffee. One could eas- ily query her on a vast range of food topics. Her particular passion, though, is barbecue—“cooking low and slow over smoldering wood.” Smoke is both an ingredient and the essential technique in the process, she says, “adding its resonance and flavor to the food.”

In an era when you can get excellent barbecue everywhere from waterfront Brooklyn (Hometown in Red Hook) to Los Angeles (Bludsoe’s in West Hollywood) to Albuquerque (Pepper’s Ole Fashion BBQ), it is difficult to imagine a time when pulled pork and ribs were rarely enjoyed outside of Texas, Kansas City, and parts of the South. Now, Aaron Franklin is a national celebrity. Bon Appétit included an Asheville barbecue joint alongside high- end dining rooms on last year’s “10 Best New Restaurants in Amer- ica” list. Smoke, traditionally reserved as a pit master’s technique, has found its way into all kinds of restaurant dishes: smoked leek soup, smoked fig-leaf shortbread, and smoked lamb khao soi. To be clear, barbecue itself is not a trend; it’s a tradition and a regional speciality with history. Brooklyn will never compare to Memphis, but in recent years, barbecue has become more popular and more broadly beloved. While Santa Fe may seem like an unlikely origin point for barbecue’s widespread popularity in restaurants and at home, one could argue that the barbecue renaissance started with the Jamisons.